Football Fever - Part One

Ron Brockway

Number 55, Right Guard

Since the end of WWII, the interest in professional and local hometown football had grown every year. The 1950s were a pivotal time for the National Football League (NFL), especially in the northeast United States. Football would soon be more popular than baseball. Players like Otto Graham, Lou Groza, Dante Lavelli, and many more made the Cleveland Browns the best team in the league at that time. The stadium in Cleveland was less than fifty miles from Spencer school, and every kid that ever wanted to play football, and his dad, dreamed of being there.

For two years, we had heard that Spencer High School was going to have a football team instead of the baseball team. Never mind that the bigger schools we would play against had four times the number of players we could muster. And never mind that we didn’t have a football field. Our fathers would take care of that.

The baseball field would remain while the team finished our opponents’ schedules and then a football field could be laid out and goal posts installed. In the meantime, our home games would be played three miles away on Geneva High School’s field at a time it didn’t infringe on their use of the field.

When I was in Junior High eighth grade the high school was able to put together a very small team of fifteen. With just fifteen players they would have only four players on the bench, which was very tiring for the players who played both offense and defense for the entire game. They lost all four games that year and didn’t score one single touchdown.

The entire student body said, “Don’t worry, we’ll get ‘em next year.”

As I entered my freshman year in high school, things looked a little brighter. Eight of the eighteen players who signed up to play had experience from the previous year. Of the ten new players, two were juniors, two were sophomores, and six, including me, came from the freshman class. Still, we lost the first two games, 45-0 and 60-0.

The third game was at “home”. About halfway into the third quarter, coach Wasulko called a time out.

After a short discussion he said, “Brockway and Petro, can you handle the left side of their line?”

We both agreed that we could.

“Evans, can you handle their center?”

“Yes, coach.”

“Then I think it’s time for the eighty-four-triple trap play.”

After Evans, the center, snapped the ball to Billman, the quarterback, he blocked the defensive center to the right. Petro and I were the guards. We pulled, went left and blocked the tackle and guard coming into our backfield. Ankrom and Bilicic our left tackle and left end, ran forward to help Billman block for Turner, the fullback. Billman handed off to Turner and then led the way through the middle of the broken defense. It worked! Fifty-five yards and a touchdown!

The parents and students went wild they made it sound as if we had just won the State Championship. Our fans had noise makers. They yelled and screamed. Someone set off a string of firecrackers, and after the game ended horns honked all the way back to the school. When the bus full of players and cheerleaders pulled in, there was a parking lot full of parents and students there to great us with screams and more honking horns. The celebration lasted into the night. We had lost 35-7, but we scored our first touchdown.

I think that touchdown inspired us to begin playing real football. We did lose the last game of the season but only by a score of 27-10.

When my sophomore season rolled around, we had added six more players from the new freshman class. We had a field with goal posts, but no bleachers. Our home games continued to be in Geneva.

We played five games that year, winning two: 7-6 at Madison and 20-0 at Thompson.

My third year in high school football almost didn’t happen. We were playing the first game of the season at Ashtabula Harbor in a Friday night game that was broadcast on WICA radio.

We had played one series of downs and punted.

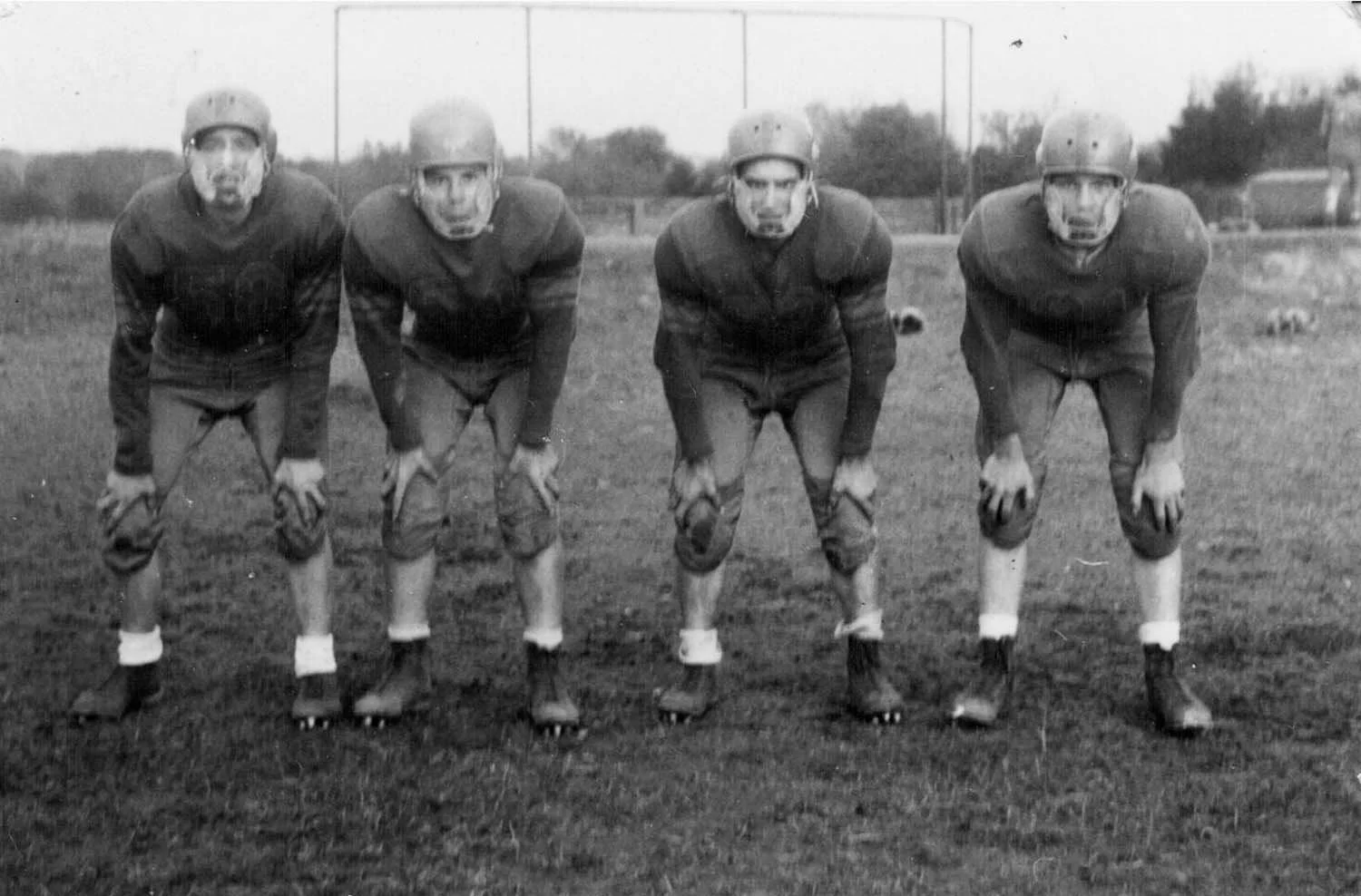

Fearsome Foursome

Ervin Hawes, Ron Brockway, Ken Ankrom, Joe Petro at practice.

Harbor’s first play was a run up the middle for a one-yard gain. I was the center linebacker and was in on the tackle. Preparing for the next play, I put my hands just above my knees, leaned forward, and fell to the ground. My hand had slid off my right knee like butter on a hot knife. I didn’t feel any pain. I looked at my knees and the right one was covered with blood. I now felt pain, not in my knee, but rather in my right hand. I looked and saw blood streaming from between my thumb and forefinger. Ervin, the right linebacker, saw what had happened and called a time out. He motioned Coach Wasulko to come in. He trotted on to the field, looked at my hand for a moment, and took me directly to the ambulance. He walked with me, holding my left arm at the elbow and asked if I felt woozy, and told me not to worry about going to the hospital.

He said, “You’ll be back in your green and gold uniform in no time.

We reached the ambulance, and he helped me in.

“See you later, Ron,” and he was gone.

We were a few minutes before leaving for the hospital while the EMT’s got the bleeding stopped. There was still a lot of dirt, grass, and lime in the wound and a lot of pain from the pressure applied to stop the bleeding.

One of the EMT’s put a shot into my hand to give me some relief from the pain.

The other told me, “Doctor Abrahms is a great doctor, and he’s on call at the hospital tonight.”

My parents couldn’t be at the game because Dad had to work. I thought Mom was probably going crazy if she heard on the radio broadcast that I had to go to the hospital with an injury.

Ralph Dorman’s dad followed the ambulance to the hospital and sat with me for a while.

Spencer is a very small and caring school. Most of us had known each other since first grade and knew each other’s siblings and parents. The players’ dads looked out for the whole team.

Mr. Dorman told me, “When I left the game, the referees were checking all the players cleats to see if one was missing. There may have been a sharp connecting screw exposed.,” he added, “Doctor Abrahams did some surgery on me. He’s great. And don’t worry about his head.”

He then excused himself to go back to the game to tell the coach and cheerleaders that I was okay, and to watch Ralph Junior play. He said he would be back again to pick me up to go home.

Soon Doctor Abrahms came in and I immediately saw what Mr. Dorman meant. His forehead had a round spot that looked as if it were a metal plate about the size of a quarter.

He caught me staring and said, “It’s a rifle shot I received during WWII while fighting in France. It went through my helmet and lodged in my forehead. Neither the bullet nor a part of the helmet could be removed. I have worn it with pride ever since.”

Cleaning the gash between my thumb and forefinger took almost an hour with a few breaks because of the pain as he pulled the skin open and rinsed away the embedded dirt, grass, and lime. My pain became more bearable every time I looked at Doctor Abrahms’ forehead.

He put in twelve stiches and a drain, then wrapped my hand in a bandage the size of a football.

He said, “Call for an appointment Wednesday or Thursday. Goodnight.”

I waited for someone to come in and tell me what was next, but no one did. So, I got off the table and started down the hallway toward the door. The highly polished terrazzo floor was as slick as ice. I had to be very careful, or I’d need the doctor again. I still had my cleats on. It sounded as if I were wearing horseshoes and skating at the same time.

I could see the door ahead of me and was almost there when the night attendant said, “Hold it right there. Your bill is here. You may pay me.”

I replied, “I don’t have money with me. Does it look like I have pockets in this uniform?”

I told her the school would take care of it. She insisted I pay before trying to leave or she would have to call security. I stood there with my mouth open not knowing what to do.

To Be Continued